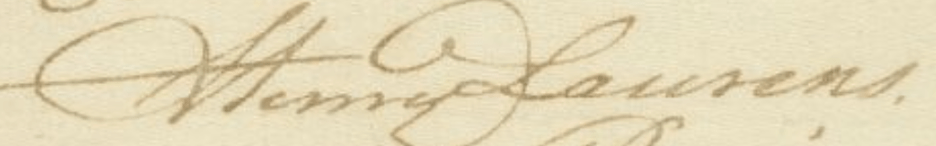

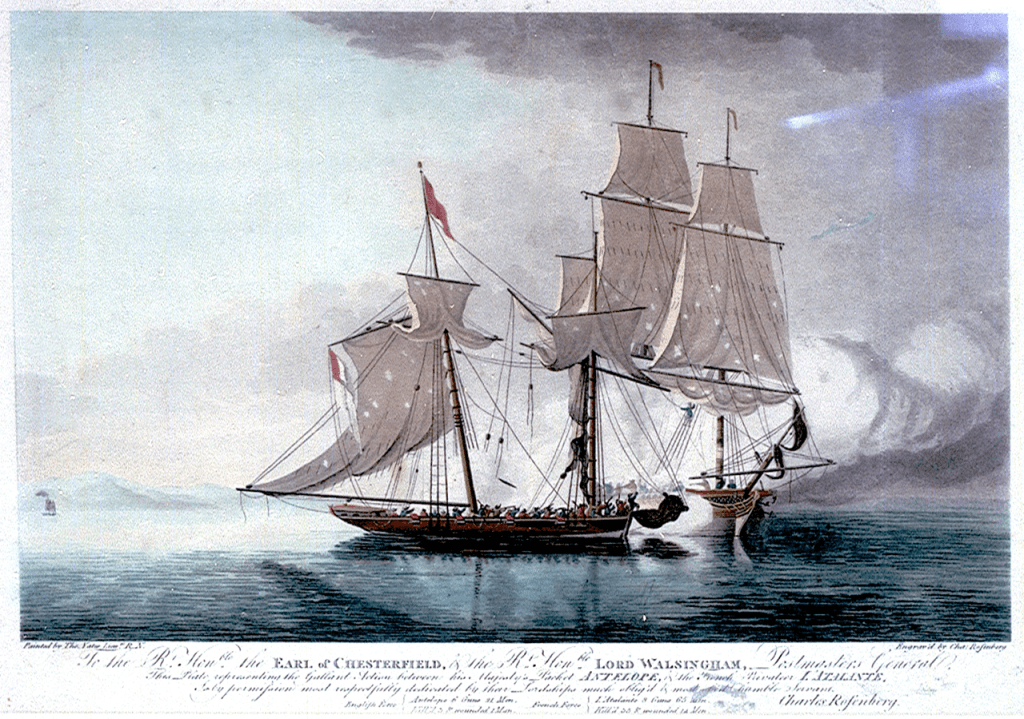

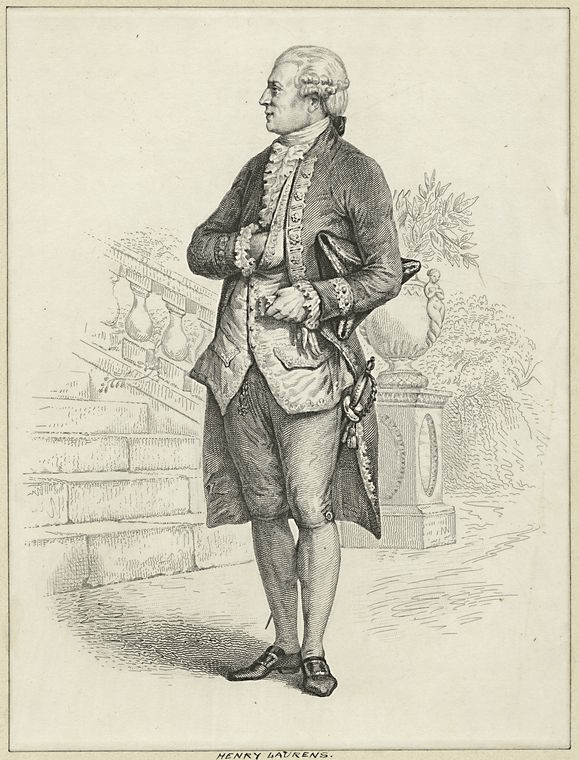

In his letter to Thomas Courtin (sometimes Curtin), Henry requests a new ship be built to transport next year’s harvest.1

Henry requests Courtin, a shipbuilder and captain, “will set about the work of building a Ship without delay” and keep “me advis’d of your proceedings” to allow me to obtain “outward freight for her.”2

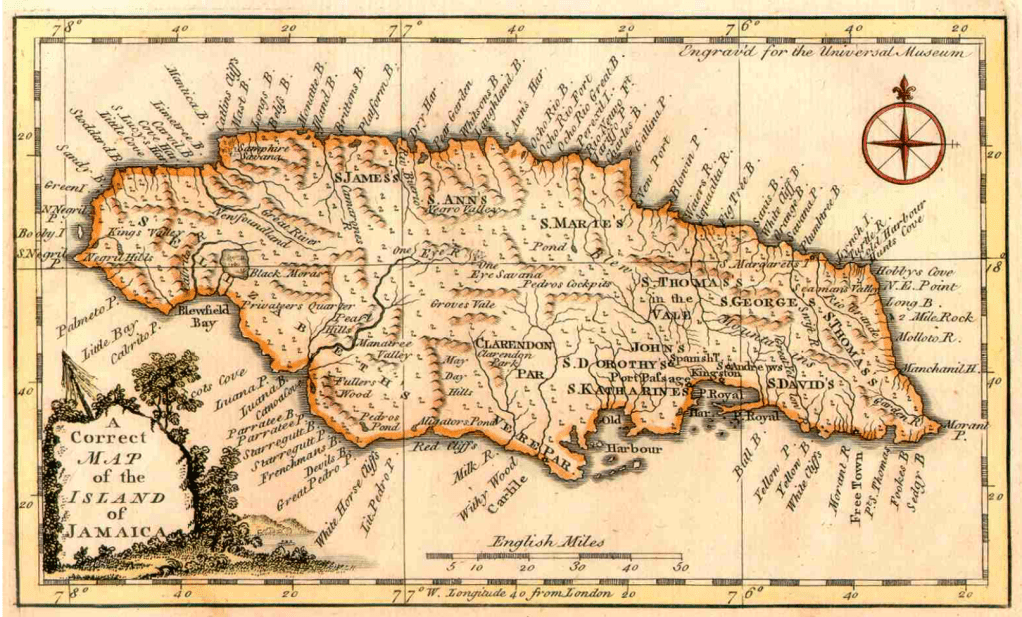

Emphasizing the importance of transatlantic connections, Henry plans to place funds “in the hands of my friends … in London, as well as” two messengers in Bristol “to keep you supply’d with Money as it shall be wanted.” But, Henry advises, “you will be as frugal as may be.”

If the money shipped on the Judith runs “against accidents,” Courtin should “apply immediately to Mrs. Nichelson & Co” for £200 Sterling.

Additionally, Henry advises that he has “Enter’d the Silver [already sent] you to the Debit of the Ship,” which shall be named Flora.

According to Dover historian Lorraine Sencicle, the vessel was built in Dover shipyard.3 It was completed and transported the Flora to Charles Town late in 1764.4

- Henry Laurens to Thomas Courtin, Charles Town, March 30, 1763, Papers of Henry Laurens, 3:390-391. All quotations from this letter. ↩︎

- Regarding Courtin as a ship captain see, The Remembrancer, Or Impartial Repository of Public Events (London, 1782), no page number. ↩︎

- Lorraine Sencicle, “Shipbuilding Part II of the Golden Age 1700-1793, http://www.doverhistorian.com (accessed March 30, 2025). ↩︎

- Henry Laurens to Maynes & Co., Charles Town, December 10, 1764, Henry Laurens Papers, South Carolina Historical Society, Charleston. ↩︎