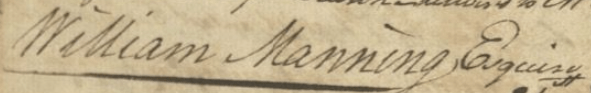

Henry Laurens penned a letter to British merchant William Manning in late February 1776. This communique, however, was not merely a commercial endeavor. As was often the case with his business associates, Laurens cultivated a friendship with Manning. Henry’s son, John, would cultivate something much more than friendship with Manning’s daughter, Martha, later that year, forcing him to marry the young woman, out of “pity.”1

But this letter was neither about John Laurens nor Martha Manning. This was a troubling report from one British subject to another: one at the empire’s periphery; the other at the imperial core. Although independence remained five months into the contingent future, war had already begun. Lexington and Concord now seemed a distant memory. The arrest the previous month of Georgia Governor Sir James Wright, a friend of Laurens’s in less timorous times, was in the recent past. And as Laurens sat in the State House that early February morning, Loyalist and Rebel forces had just clashed at the Battle of Moore’s Creek Bridge, in modern Currie, North Carolina.2

The omnipresence of war filled Henry’s pen that dank morning. “Every day,” he wrote, “leads us … deeper and deeper into warlike preparations … matches & ball all in readiness even for a midnight defense.” He assured his friend, in typical Gamecock style, that South Carolinians preferred torching their own town to allowing a “cruel enemy” access. Hyperbole for sure, but he insisted that men were prepared to “oppose at all hazards the unjust attempts of the ministry … to involve us all in the horrible scenes of foreign and domestic butcheries.” And he did not mean war. The “foreign and domestic” foes resided amongst and near Carolinians.

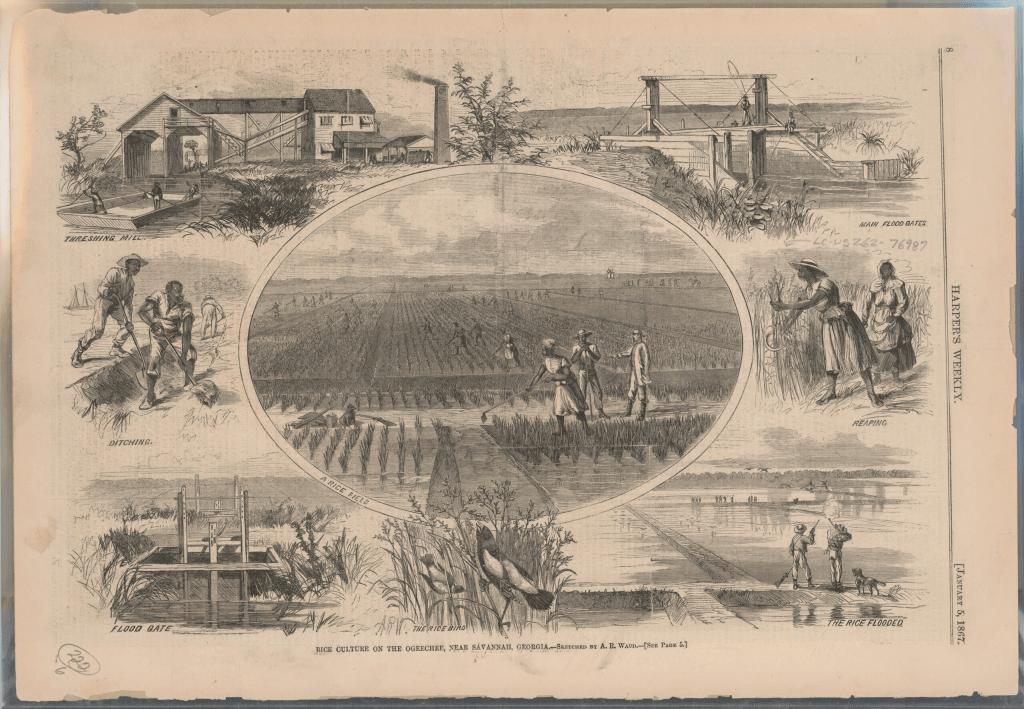

Although Henry was concerned about the threat of British men-of-war assaulting Charles Town’s front, he was most worried about the possibility of Native Americans “on our backs [and] Tories and Negro Slaves to rise in our bowels,” all such events, he assured Manning, were playing out in Georgia.3 Unaware of the deep psychology at play, within his own psyche, Henry maintained that Carolinians “will save [Britain] the trouble to manumit & set free those Africans whom she captivated, made slaves, & sold to us.” In short, enslavers “ready … to do every thing in their power” to resist British tyranny.” Cognitive dissonance activated. Months later, Thomas Jefferson echoed this painfully ironic statement.

In their argumentation against supposed British tyranny, men like Henry and Jefferson sought to capitalize on the moral high ground. Of this cognitive dissonance, historian Peter A. Dorsey observed: “Slaves may have symbolized what England threatened to do to the colonies, but white Southerners also believed that enslaved Americans, acting on the same values Whigs professed, were at least as dangerous.”4

- Henry Laurens to William Manning, Charles Town, February 27, 1776, in Papers of Henry Laurens, 11:122-128. For the nuptials, see John Laurens to Henry Laurens, London, October 26, 1776, in ibid., 11:275-278. For the pitiful nature of those nuptials, see John Laurens to James Laurens, London, October 25, 1776, Henry W. Kendall Collection, New Bedford Whaling Museum, Sharon, Massachusetts. ↩︎

- For Lexington and Concord, see Walter Borneman, American Spring: Lexington, Concord, and the Road to Revolution (New York, 2015). For the capture of Governor Wright, see Greg Brooking, From Empire to Revolution: Sir James Wright and the Price of Loyalty in Georgia (Athens, 2024). For the battle, see Roger Smith, “The Failure of Great Britain’s ‘Southern Expedition’ of 1776: Revisiting Southern Campaigns in the Early Years of the American Revolution, 1775-1779,” The Florida Historical Quarterly 93, no. 3 (Winter 2015): 387-414. ↩︎

- For the interplay of Natives, Blacks, and the British, see Jim Piecuch, Three Peoples, One King: Loyalists, Indians, and Slaves in the Revolutionary South, 1775-1782 (Columbia, 2013). ↩︎

- Peter A. Dorsey, “To ‘Corroborate Our Own Claims’: Public Positioning and the Slavery Metaphor in Revolutionary America,” American Quarterly 55, no. 3 (September 2003), 378 and 356. ↩︎

Discover more from Greg Brooking, PhD

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.