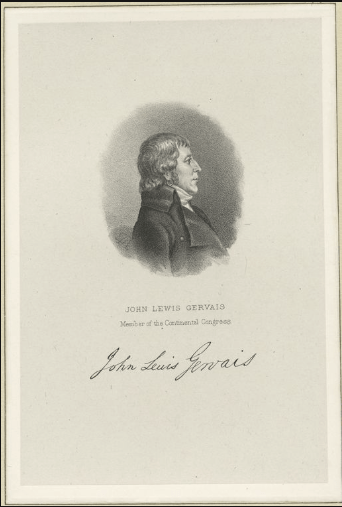

On this Saturday from Charles Town, Henry penned a letter to Richard Clarke, a well-respected priest sent to the city by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel.1 He arrived in Charles Town in the fall of 1753. “When he preached,” wrote David Ramsay, “the church was crowded, and the effects of it were visible in the reformed lives of many of his hearers.”2

He left South Carolina in 1759 and became lecturer at St. James’s Aldgate in London. “Though that city abounded with first-rate preachers,” Ramsay continued, “his eloquence and piety attracted a large share of public attention.” Furthermore, and most relevant to this letter, “He was so much esteemed and beloved in Charlestown, that several of its inhabitants sent their children after him, and put them under his care and instruction at an academy which he opened near London.”3

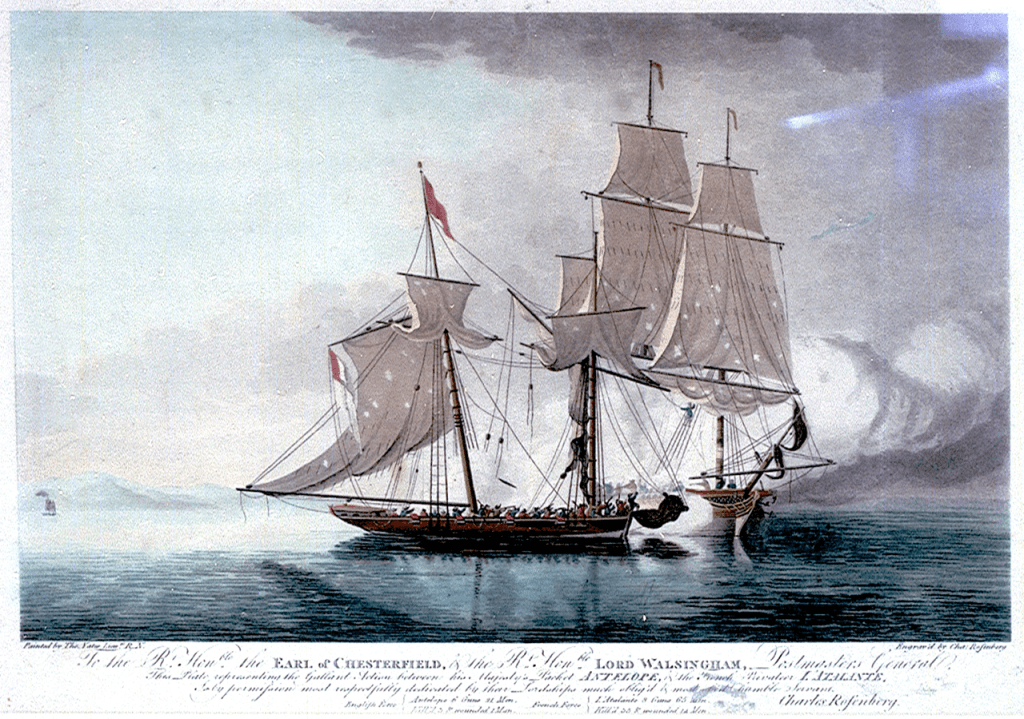

“I have now been long waiting in anxious Suspense for an Answer to a Letter … upon very great Importance to me, and” which you should have received in October. “In the mean Tim, Henry writes, “I have determined with God’s Will to send my second son Henry to your school, and to board in your House.” Henry said he would send Henry in a couple of weeks aboard the Indian King, captained by Richard Baker, “a very careful kind Man.”

Upon his arrival at Cowes, Henry’s friends will convey him to London, but only after he has been “Innoculat[ed] for the Small Pox.” Henry adds that his brother, James, plans to send his wife’s nephew on the same ship.

Henry also had plans for his son, John, who would accompany him to England in “a Month or two longer.” Henry and John would depart for England that July, arriving at Falmouth on October 9 via Philadelphia.4 “Last night,” he wrote a London friend, after a Passage of 29 days …, I arrived here in good health, having in company with me … my eldest and youngest sons, and a Servant (an enslaved man named Scipio). The servant insisted on being called Robert Laurens while in England.5

- Henry Laurens to Richard Clarke, Charles Town, March 16, 1771, Papers of Henry Laurens, 7:457-458. ↩︎

- David Ramsay, History of South Carolina, From Its First Settlement in 1670 to the Year 1808 (Newberry, 1858), 250. ↩︎

- All quotes in this chapter, ibid. For his departure see, South Carolina Gazette, February 17, 1759. ↩︎

- Henry Laurens to Richard Clarke, Charles Town, March 16, 1771, Papers of Henry Laurens, 7:457-458. ↩︎

- Henry Laurens to William Cowles, Falmouth, October 10, 1771, Papers of Henry Laurens, 8:1. ↩︎