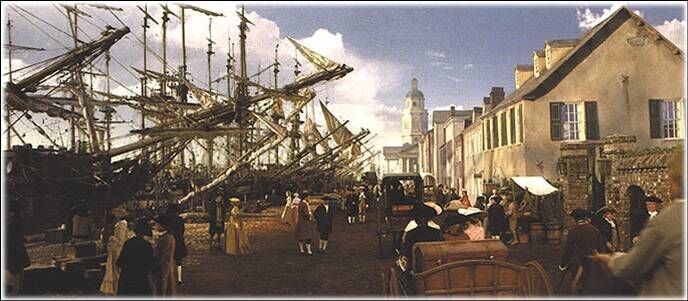

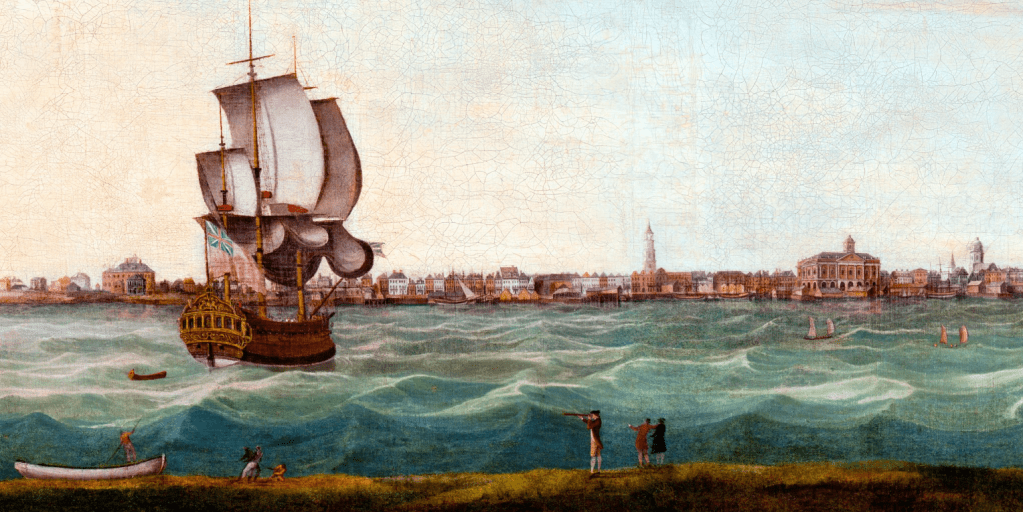

Henry accepted William Henry Drayton’s offer to assist the “smaller Armed Vessels” in Charles Town harbor with the Prosper.1 Henry said the Council of Safety (the 2nd such council in South Carolina), of which he was the president) had judged it to be “very necessary for the public service immediately to equip these Vessels for Cruizing on the Coast [and] we desire you will order Thirty such Men on board the Brig[antine] Comet,” under the command of Captain Joseph Turpin, part owner of the schooner Molly.2

There was reason for concern these days. British vessels had been spotted off the coast of Charles Town and Savannah in January and February. Their presence off the coast of Savannah the previous month had compelled Georgia’s Council of Safety to arrest royal Governor Sir James Wright.3

British vessels remained off the Lowcountry coast for months, engaging Georgia’s Rebels in the Battle of the Riceboats (Rice Boats) in early March before attacking Charles Town (Fort Sullivan) at the end of June.4 Although the Georgians lost the Battle of the Riceboats, South Carolinians, led by Colonel William Moultrie, repelled the British offensive.5 The fort was renamed Fort Moultrie shortly after the battle.

- Henry Laurens to William Henry Drayton, Charles Town, February 26, 1776, Papers of Henry Laurens, 11:121-122. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- Greg Brooking, From Empire to Revolution: Sir James Wright and the Price of Loyalty in Georgia (Athens, 2024), ch. 6. ↩︎

- Ibid., 152-154. ↩︎

- Jim Stokely, Fort Moultrie: Constant Defender (Washington, 1985); David Wilson, The Southern Strategy: Britain’s Conquest of South Carolina and Georgia, 1775-1780 (Columbia, 2005), ch. 4; John Buchanan, The Road to Guilford Courthouse: The American Revolution in the Carolinas (New York, 1997), ch. 1. ↩︎